According to the ancient Jewish historian Josephus and the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria, the Essenes were indeed celibate.1 The Roman philosopher and naturalist Pliny the Elder agrees and seems to locate an Essene community at Qumran. The question, of course, is whether the Qumran community was in fact Essene.

The Essenes were a Jewish religious group, like the Pharisees and the Sadducees (and a number of other smaller ones). Whether the Qumran community was Essene is a much-debated question. According to a recent comprehensive review of Dead Sea Scroll research by leading Israeli Scroll scholar Devorah Dimant, the Qumran community probably was Essene.2 “In my judgment,” she writes, “the fundamental identity has stood the test of time.” But that doesn’t tell us whether the Qumran community, even if Essene, was celibate.

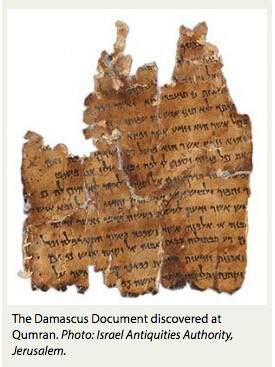

Tending in the opposite direction, two major Dead Sea Scrolls, the Damascus Document and the Rule of the Congregation (1QSa I), speak of women and children. The Damascus Document spells out special rules for a community consisting of families.

In the end, the question of the Qumran community’s celibacy remains just that—a question or “a thorny problem,” as Dimant characterizes it. “Unsolved difficulties remain.”

And this is just one of the remaining difficulties concerning Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls, which over time have multiplied rather than resolved, in Dimant’s view. What seemed clear in early analyses now seems more complicated. Perhaps, for example, there were two Dead Sea Scroll groups or one group with two aspects—one apocalyptic reflecting commonalities with later Christian groups and one more halakhic or legal, reflecting commonalities with contemporaneous Judaism.

The nature of the Qumranites’ relationship with contemporaneous followers of Temple Judaism is another matter that must now be treated with more subtlety, Dimant believes. The break is not so clear-cut.

hat is clear, however, is that the Qumranites adopted a 365-day calendar, rather than the lunar calendar of Temple (and modern) Judaism. This meant that the Qumranites observed holy days on different dates than followers of Temple Judaism. This is not unique, however; the 365-day calendar is also found in other texts such as 1 Enoch, which is a nonsectarian text. In Dimant’s view, the Qumranites’ different calendar does not necessarily imply a religious schism. She quotes the British Qumran scholar Sacha Stern approvingly: “The notion that the calendar was critical to Qumran sectarianism remains no more than a modern scholarly assumption.” Dimant goes on to wonder whether terms such as “schism” and “rift” are really “appropriate” when describing the relationship between the Qumran group and mainstream Temple Judaism.

This introduces another kind of scholarly divide—between those who emphasize the apocalyptic aspect of the scrolls and find a strong similarity to “the beliefs and organization of early Christian groups” and those who, in contrast, emphasize the Qumranites’ devotion to halakhah (legal rules), as illustrated by six partially surviving copies of the so-called Halakhic Letter (4QMMT) that lists legal disputes mainly concerning cultic purity between the Qumran group and presumably mainstream Judaism. (Incidentally, BAR was successfully sued in an Israeli court for copyright infringement by Ben Gurion University scholar Elisha Qimron for publishing his reconstruction of MMT prior to his official publication of it.) Another Qumran commitment to Jewish halakhah is reflected in the Temple Scroll, the longest of all the Dead Sea Scrolls, which is in the form of a divine address to Moses concerning the construction and operation of the Temple. It is entirely confined to legal matters.

In the end, Dimant refers to the “unsettled scene of Qumran research.” The issues are complex; Dimant cautions against “the reaching of sweeping and simplistic conclusions.”